Special Thanks to :

http://www.onmarkproductions.com/html/buddhism.shtml

http://www.onmarkproductions.com/html/buddhism.shtml

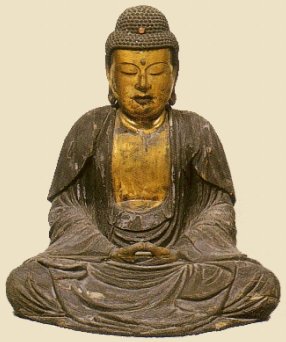

Shaka Nyorai, Enlightened One Shaka Nyorai, Enlightened OneShaka, Shakyamuni, Sakyamuni Gautama Buddha, Prince Siddhartha Founder of BuddhismCLICK HERE FOR GUIDE TO BUDDHA’S TEACHINGS

SHAKA NYORAI (BUDDHA) AND THE ORIGINS OF BUDDHISM Buddhism originated in Northern India, or present-day Nepal. It was here that the Historical Buddha (aka Prince Siddhartha, Gautama Buddha), was born and lived in the sixth century BC. In China, his contemporaries were Confucius and Lao-tzu (the founder and “old boy” of Chinese Taoism), and slightly later in the West comes Plato (approx. 427 - 347 BC). When Buddhism arrived in Japan in the 6th and 7th centuries AD via Korea and China, Siddhartha became known in Japan as Shaka or Shakamuni, which means “Sage of the Shaka Clan” (his actual birth clan). In Japan, Shaka Nyorai (translated as Shaka Tathagata or Shaka Buddha) is venerated widely among most Buddhist sects, with the exceptions of the Jōdo Shinshū 浄土真宗 Sect (New Pure Land Sect, which revers Amida Nyorai) and the Shingon school of Esoteric Buddhism (which revers Dainichi Nyorai). Nonetheless, Shaka is honored as one of the 13 Deities 十三仏 (Jūsanbutsu) of the Shingon Sect. In this role, Shaka presides over the memorial service held on the 14th day following one's death.

Mantra for Shaka Nyorai = naamaku saamanda bodananbaku

EARLY BUDDHIST ART

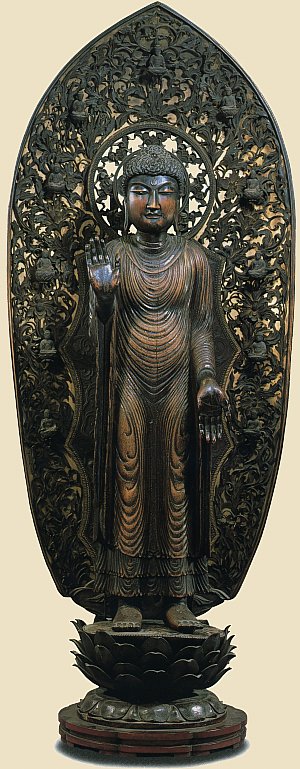

For four centuries after Gautama’s death, legends and facts about the historical Buddha, his dialogues and his sayings, were preserved only in the memories of monks and followers. There were no written records or artistic representations. Like the Hindu Brahmins, the early Buddhists believed that religious knowledge was too sacred to be written down, too sacred to be etched in stone or wood. In those early years, when overt representations of the Buddha image were taboo, the main artistic vehicle for symbolizing the Buddha’s presence was to show the Buddha's “footprint.” These footprints of early Buddhist artwork can be found throughout Asia, often in narrative reliefs depicting key episodes in the Buddha's life, and thereby indicating his personal presence. These footprints are often engraved with various Buddhist symbols (Click here for many more details about this topic). One of the most frequently used symbols in early Buddhism was the Svastikah 卍 -- which many centuries later is unfortunately misappropriated by Nazi Germany.  Identifying Shaka Sculptures. Statues of Shaka Nyorai and other Nyorai (Buddha) share common attributes. These include elongated ears (all-hearing), a bump atop the head (Skt. usnisa, all-knowing, bump of knowledge), and a boss in the forehead (Skt. urna, third eye, all-seeing). Among the many sculptural depictions of the various Nyorai (Buddha), some rules of thumb can help you to identify the historical Buddha. First, the Shaka Nyorai nearly always wears a simple monk’s robe, and is seated or standing on a lotus flower. This isn’t enough to identify the statue as Shaka, however, as the same guideline applies to most Nyorai (those who have attained Buddhahood). The Nyorai are typically portrayed wearing simple clothing, without accessories, jewelry, or weapons. A second way to identify Nyorai statues is to look at the positioning of the hands. Two of the most common hand gestures (mudra) of Shaka Nyorai are the “Fear Not” Mudra (right hand held up) and “Blessing Mudra” (left hand pointing downward). Another common mudra portrays Shaka Nyorai with his left palm up and fingers outstretched (except the middle two, which may be curled in slightly to beckon people toward salvation), while the right hand is often, although not always, shown with the thumb held between the other four fingers (holding tightly to those who seek salvation). A knowledge of these hand gestures -- called “mudra” in Sanskrit -- can help you identify and distinguish among the various Nyorai. The five most widely known mudras, moreover, correspond to five defining episodes in the life of the Historical Buddha. Nonetheless, mudra traditions vary greatly, and often it is impossible to identify statues based on mudra alone.

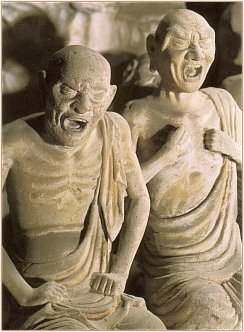

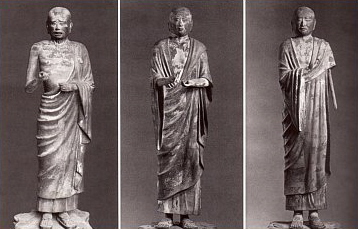

Jō-roku (or joroku) is equivalent to roughly 4.8 meters. Many “standing” sculptures in the early years of Japanese Buddhism are made to this specification. Jo is a unit of length, about three meters, and Roku means “six,” and this refers to six shaku (shaku is another Japanese unit of length, about 0.30 meters). Thus, Jo-roku is equivalent to roughly 4.8 meters. According to some Japanese legends, the Historical Buddha was actually that tall. Historical Notes In mainland Asia, less so in Japan, the Shaka Nyorai is pictured seated on a lotus with four petals, representing the four great countries of Asia (India, China, Central Asia, and Iran) during the early centuries of Buddhism’s introduction. The lotus is a symbol of purity. Although a beautiful flower, the lotus grows out of the mud at the bottom of a pond. The Buddha is an enlightened being who "grew" out of the "mud" of the material world. Like the lotus, the Buddha is beautiful and pure even though he existed in the material world. Buddhism developed in India in the sixth century BC and gradually spread throughout Asia. However, it wasn’t until the Asuka Period (522-645 AD) that Buddhism arrived in Japan via Korea and China. Most of Japan’s earliest Buddhist sculpture and artwork were imported from mainland Asia, or made by Chinese and Korean artisans living in Japan. These old sculptures look almost exactly the same as their Chinese and Korean counterparts -- one defining characteristic of these early sculptures is the “skinniness” or non-human-ness of the statues (see two photos below of Shaka Trinity).

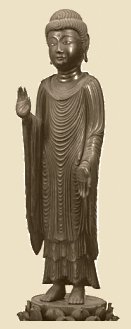

Wood, Height = 162.67 cm Yosegi Zukuri Carving 寄木造 (Assembled Wood) Kirikane 截金 Decorative Technique (see note below) Treasure of Seiryouji Temple 清凉寺 (Kyoto) Photo Courtesy: National Treasures of Japan 日本の国宝 Magazine, Published 8 July 1997 by The Asahi Shimbun

Says JAANUS About Seiryōjishiki Shaka 清凉寺式釈迦

Abbreviation of Seiryōjishiki Shaka Nyoraizō 清凉寺式釈迦如来像, also known as Zuizō Shaka 瑞像釈迦. A sculpture of Shaka modeled after the Shaka image Shakazō 釈迦像 at Seiryōji Temple 清凉寺 (popularly known as Saga Shakadō 嵯峨釈迦堂) in Kyoto. The Seiryōji image itself was brought from Northern Song China to Japan by the Tōdaiji 東大寺 priest Chōnen 奝然 in 987 AD. Copies of this image were made for temples all over Japan. Seiryōjishiki Shaka is a generic term for all such images.    Seiryōjishiki Shaka 清凉寺式釈迦 Left = Original statue brought from China to Japan in 987 AD Middle & Right = Copies made in Kamakura period

LEGEND ABOUT SEIRYOUJI STATUE. According to texts brought from India to China in the 5th and 7th centuries, Mahayana traditions claim that two statues were made of the Historical Buddha soon after his death. The statues were supposedly commissioned by Prasenajit and Udayana, two Indian kings who were Buddha’s faithful disciples. One was made in gold, the other of red sandalwood. The second image, based on the legend, was carried off to China in the early 5th century, and then, in later centuries, it was stolen by a visiting Japanese monk who replaced the original with a clever copy. Seiryouji Temple 清凉寺 in Kyoto claims to be the owner of this statue, which it says provided the model by which all other statues of the Historical Buddha (Shaka) were modeled. This legend has been debunked, however, for the Seiryouji Shaka image has been clearly dated to 987 AD.

Note About Kirikane (Kirigane) 切金. Also written 截金. Literally "cut gold." A decorative technique used in Buddhist artwork to adorn Buddhist statues. The technique came from Tang China, arriving in Japan sometime in the 7th century. Leaves/sheets (haku 箔) of gold or silver (sometimes other metals) are pressed together, cut into long thin strips or other shapes, then affixed to the surface of a statue or painting. A related term is kirihaku 切箔, which refers to a decorative metal pattern on sculptures or paintings. Kirikane was a popular technique in the Heian period for sculpture and painting. But it fell into decline during the Kamakura period, replaced by the use of gold paint (kindei 金泥) for creating the decorative gold outlines and patterns. Kirikane also refers to a decorative method popular in the Kamakura period for adorning lacquer statues with cut metal. For more techniques on making statues, see the Materials and Techniques Glossary for Making Buddhist Statuary. According to Indian legend, the first two Buddha sculptures in the world were made from Indian sandalwood and “purple gold” (a gold of the highest quality, which gives off a purple sheen). Once, it is said, Sakyamuni Buddha left this world to deliver a sermon to his mother, who resided in the Trayastrimsa Heaven. During the Buddha’s absence, King Udayana began yearning for him, and so made a sandalwood statue of his beloved teacher. This sculpture was widely known among Buddhist followers as the Udayana Sandalwood Sakyamuni and was the object of great admiration. This Buddha figure was later transported to Quici (now Kuche), then was moved again in the year 401 AD to the Chinese city of Chang’an (current day Xian), where many copies were made. With the arrival of this sculpture, sandalwood images came to be quite widely produced even within China and many records of the production of such Buddhist sculptures survive from the second half of the 5th century.   Black Shaka Nyorai with Headdress Jufuku-ji -- Zen Temple in Kamakura This is unusual, as Shaka statues are typically unadorned

Statues of the Nyorai are not typically shown with accessories (e.g. crown, jewelry). But in some Zen temples (such as Jufukuji and Kenchoji and Shuzenji in Kamakura), Nyorai statues wear a crown atop the head. Zen Buddhism worships the Historical Buddha as well as the Birushana Nyorai -- the latter is often portrayed with a crown, and the Historical Buddha is sometimes shown as a manifestation of Birushana. Not sure why it is black though. Since Zen worships the Kegon-kyo (Garland Sutra), the answer may lie there.

Why are there so many Buddhas ?

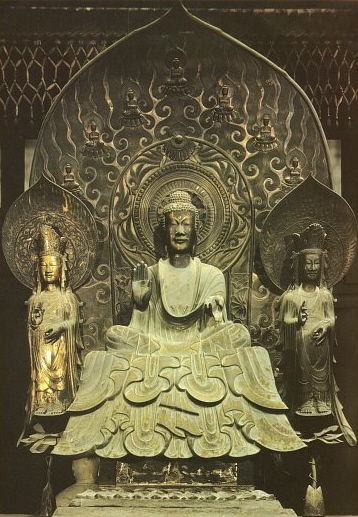

The form of Buddhism that came to Japan in the Asuka Period, however, was known as Mahayana Buddhism. Unlike the Theravada school, which was limited to a small “select” group of followers who sacrificed all to pursue its harsh monastic regimen as monks, the Mahayana school aimed to bring salvation to the common people. In Mahayana Buddhism -- unlike Theravada -- each and every living person can attain Buddhahood, not just the monastic community. To Mahayana practitioners, many people have achieved enlightenment over countless ages, and the Historical Buddha (i.e.Shaka Nyorai) is just one of many enlightened beings. Thus numerous Buddha and Bodhisattva populate the Mahayana pantheon. For a discussion of the difference between Theravada and Mahayana Buddhism, please click here.  Famous bronze Shaka Trinity, 632 AD Height = 86.4 cm, Hōryūji Temple 法隆寺 in Nara Surrounded by two attendants (thought to be Yaku-ō Bosatsu & Yakujō Bosatsu). Early Buddhist images have elongated faces & hands. See Early Japanese Statuary. Learn more about Buddhist statuary in 7th-century Japan.  Closeup of above photo’s background frame Closeup of above photo’s background frame

Major Episodes in Artwork of Shaka

Text courtesy of www.art-and-archaeology.com/india/glossary1.html The life of Buddha began to be represented in art sometime before 100 AD. The major episodes are:

Buddha was a contemporary of Mahavira, the founder of Jainism, and there are many intriguing parallels between the two religions.

Theravada Buddhism emphasized the difficulty of attaining salvation, and advocated meditation and the monastic life as the means to salvation for a chosen few. This view was challenged by the Mahayana ("Greater Vehicle") school, who proclaimed the existence of numerous Buddhas and Bodhisattvas as universal saviors. Buddhism died out in India around 1200 AD, succumbing to Muslim invasions as well as a resurgent Hinduism. However, by this time the religion had spread via the trade routes to east and southeast Asia, where it took root and has flourished up to the present day.

Mythical Home of Shaka Nyorai

Mt. Shumisen (Mt. Sumeru, Mt. Meru) is the mythical home of Shakya Nyorai (the historical Buddha). According to Buddhist lore, Mt. Sumeru is located at the center of the world, surrounded by eight mountain ranges, and in the ocean between the 7th and 8th there are four continents inhabited by humans. These four continents are protected by the Shitenno, with each leading an army of supernatural creatures to keep the fighting demons (Ashura) at bay. On the top of Mt. Sumeru is the heavenly palace of Shakya Nyorai, and the abode of the Trayastrimsha (33 Gods) ruled by Taishakuten.

Transmigration of Souls & Reincarnation

The Six States of Existence Buddhist teachings incorporate countless manifestations of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas. To Buddhists, the transmigration of souls from one creature to another has continued unabated for aeons. Those reaching full enlightenment are few, for the path to awakening is long and arduous. But the path is not closed, and in any period, one or more -- or none at all -- may appear. It is said that Gautama (Siddhartha, Shaka, the historical Buddha) did not attain enlightenment in one life time, but rather struggled over many lives and through numerous incarnations to finally become a Bodhi-being. In some Buddhist traditions, the term Bodhisattva actually refers to Guatama Buddha prior to his enlightenment -- including the countless lives he passed through en route to Buddhahood. These earlier lives are called the Jatakas (birth stories), and they are a very frequent subject of Buddhist lore and art. There are six states of existence before one reaches Buddhahood. The lowest three states are called the three evil paths, or three bad states. They are (1) people in hells; (2) hungry ghosts; (3) animals. The highest three states are (4) Asuras; (5) Humans; (6) Devas. All beings in these six states are doomed to death and rebirth in a recurring cycle over countless ages -- unless they can break free from desire and attain enlightenment. Click here for Japanese spellings of the six states.

Kanbutsu-e 潅仏会Ceremony to Commemorate Buddha’s Birthday

Text courtesy of www.aisf.or.jp/~jaanus/deta/k/kanbutsue.htm. A ceremony held every year to commemorate Buddha's birthday, April 8th, where a small statue of Buddha is sprinkled with scented water or hydrangea tea. The ceremony recreates a legend that when the Buddha was born he was sprinkled with perfume by the dragon god (ryuuou 竜王). A small shrine, known as the hanamidou 花御堂 is set up and decorated with flowers. A small image of the Buddha in the form of a child as he appeared at birth (tanjoubutsu 誕生仏; see below), is placed on a wide, shallow metal bowl, known as the kanbutsu-ban 潅仏盤. The statue of Buddha has the right hand held up, and the left hand pointing down, depicting the moment when Buddha took seven steps forward and pronounced the words “Tenjou tenga yuiga dokuson 天上天下唯我独尊“ (I alone am honored in heaven and on earth). Visitors to the temple where the ceremony is performed use a small ladle to sprinkle scented water over the top of the statue. The kanbutsu-e ceremony was brought to Japan from China, and the first recorded celebration in Japan was at Gankouji 元興寺 in Nara in 606. It spread to become a regular part of Buddhist tradition in other temples, the court, and among ordinary citizens. A famous Kanbutsu-ban decorated with hunting scenes is preserved in Nara's Toudaiji 東大寺. It dates from the Nara Period and shows outstanding metal craftsmanship.

Tanjoubutsu 誕生仏 or Buddha’s Birth

Text courtesy of www.aisf.or.jp/~jaanus/deta/t/tanjoubutsu.htm. Lit. Buddha at birth. A sculptural representation of the historical Buddha Shaka 釈迦 immediately after his birth. According to legend, his mother Mahamaya gave birth to him from her right side. The infant then took 7 steps and, pointing to the heavens with his right hand and to the earth with his left hand, proclaimed, "I alone am the honoured one in the heavens and on earth." The tanjoubutsu show the infant Shaka in this pose, usually wearing a loincloth. Shaka's birth is counted among eight major events in his life (Shaka Hassou 釈迦八相), but statuary representations of this type are rare outside of Korea and Japan. Elsewhere the infant Shaka is generally depicted in reliefs and murals with both arms hanging at his side or with the right hand raised in the “mudra bestowing fearlessness” (semui-in 施無畏印). In Japan images in bronze (and occasionally in wood) between 5-20 cm in height are very common because they have becomes a requisite for the kanbutsu-e 潅仏会 or “rite for sprinkling” (an image of) the Buddha. The rite is performed annually on the 8th day of the 4th month in celebration of Shaka's birthday, when a tanjoubutsu statuette is placed in a shallow bowl, kanbutsuban 潅仏盤 inside a small shrine decorated with flowers, hanamidou 花御堂 and is sprinkled by worshippers usually with sweet hydrangea tea, amacha 甘茶 in imitation of the 2 dragon-kings who are said to have poured perfumed water on Shaka when he was born. This rite, which may be traced back to the 7th c., is today more commonly known as hanamatsuri 花祭り or ”flower festival.” Tanjoubutsu date from as early as the Asuka period, but the most renowned is at Toudaiji 東大寺 (Nara; national treasure). Other representative examples include those at Goshinji 悟真寺, Nara (Hakuhou period ), Zensuiji 善水寺, Shiga prefecture (Nara period), and Daihouonji 大報恩寺, Kyoto (Kamakura period).

Shaka Hassou 釈迦八相

Text courtesy of www.aisf.or.jp/~jaanus/deta/s/shakahassou.htm Lit. eight phases (or aspects) of Shakamuni 釈迦牟尼. Also referred to as hassou joudo 八相成道 ("eight-phase attainment of the path"), hassou jigen 八相示現 ( "manifestation of the eight phases"), or simply hassou 八相 ( "eight phases"). The eight major events in the life of the historical Buddha, Shakyamuni (Shaka 釈迦), that constitute a popular format for artistic representations of Shakamuni's life (butsuden-zu 仏伝図). The practice of selecting eight particular events in which to encapsulate the course of Shakamuni's career is thought to have been established in China. There are several traditions regarding the events constituting the "eight phases." Probably the most common one is derived from the SIKYOUGI 四教義 (Ch: Shjiaoyi; "The Meaning of the Four Teachings") by Zhiyi 智顗 (Jp :Chigi; 538-597). Its eight parts include:

In another tradition, based on the DACHENG QIXIN LUN 大乗起信論 (Jp: DAIJOUKISHONRON: "Treatise on the Awakening of Faith in the Great Vehicle"), (5) gouma is omitted and jutai 住胎 (abiding in his mother's womb) added after (2) takutai. The hassou joudo places the central importance in Shakamuni's life on his attainment of enlightenment (6). In Japan, sets of images of these "eight phases" are recorded as having been enshrined in, for example, the East and West Pagodas of Yakushiji 薬師寺 (Nara) although these particular examples are no longer extant. There are, however, many examples of paintings depicting these eight scenes: those depicting either Shakamuni's enlightenment or his death in the center, with the remaining seven events on the periphery, are known as Shaka hassou joudo-zu 釈迦八相成道図 ("painting of Shakamuni's eight-phase attainment of the path") and Shaka hassou nehan-zu 釈迦八相涅槃図 ("painting of Shakamuni's eight-phase nirvana"; see nehan-zu 涅槃図) respectively. A renowned example of the former is preserved at Daifukudenji 大福田寺 (Mie prefecture) and equally renowned examples of the latter are found at Manjuji 万寿寺 (Kyoto) and Tsurugi Jinja 剣神社 (Fukui prefecture). Didactic works such as the SHAKA HASSOUKI 釈迦八相記 ("Account of the Eight Phases of Shakamuni") and SHAKA HASSOU MONOGATARI 釈迦八相物語 ("Story of the Eight Phases of Sakyamuni"), aimed at the general populace, utilized these "eight phases" as a convenient device for teaching the salient points in the story of Shakamuni's life.

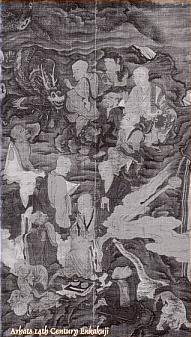

(Jūroku Zenjin, Juroku Zenjin 十六善神). Protectors of the Daihannyakyō Sutra 大般若経 (Great Widsom Sutra, Skt. Mahaprajna paramita sutra) and those devoted to it. But more accurately referred to as the 16 Protectors of Shaka Nyorai (the Historical Buddha), or Shaka Jūroku Zenshin 釈迦十六善神, or Shaka Sanzon Jūroku Zenshin 釈迦三尊十六善神. They are depicted as warlike figures (Yasha 夜叉), and paintings of the sixteen were invoked at the Daihannya-e 大般若会 ceremony. They often appear in the Sangatsu-kyō Mandala devoted to Shaka. In Japan, the 16 are also shown around Hannya Bosatsu 般若菩薩, who is sometimes invoked instead of Shaka during the Daihannya-e service, which involves the ritual reading of the 600-fascicle Hannyakyō 般若経 sutra (translated into Chinese by Xuanzang 玄奘 (Jp. = Genjō) in the 7th century AD.

Says JAANUS: “The Sixteen Protectors of Shaka are a specific group of warlike figures (yasha 夜叉) believed to be the protectors of the DAIHANNYAKYOU 大般若経. In art, Shaka, with the mudra of either tenbourin-in 転法輪印 or seppou-in 説法印, is attended by the two bodhisattvas Fugen 普賢 and Monju 文殊. The Sixteen Protectors appear in two groups of eight to either side and in front of the principal figures. They are believed to guard the sutra and those who uphold it. Paintings of the Sixteen Protectors were hung as central images for ceremonies called Daihannya-e 大般若会 at which there was a tendoku 転読 (flipping through pages, or opening scrolls, and reading the chapter headings at breakneck speed) of the text a certain number of times. The earliest record of commissioning a painting for a ceremony dates from 1114, while the earliest extant paintings date from the third quarter of the 12th century.

LEARN MORE

|

|

No comments:

Post a Comment